Toward Which We Have Striven

The Planning of D-Day

The largest land, sea, and air invasion ever attempted was years in the making. World War II in Europe began with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in September 1939. Britain and France declared war in response but could do little to help the Poles. In the spring of 1940, German leader Adolf Hitler staged successful invasions of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, and other nations. German armies then moved into France, rapidly breaking through border defenses and pinning much of the British and French armies against the English Channel. While Britain was able to evacuate many of those forces from the area around Dunkirk, it left Nazi Germany dominant on the continent of Europe.

Almost immediately, British leaders began envisioning ways to get back across the Channel in an amphibious assault, eventually code-named Operation Overlord. Understanding the threat such an invasion would pose, Hitler began to build formidable defenses along the entire Channel coast, which he called his “Atlantic Wall.”

In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, formerly a partner. Also, by the end of that year, the United States entered the war after Japan (an ally of Germany) attacked the American base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The entry of the U.S. into the Alliance meant the scope of the planned cross-Channel invasion would grow. Soon American forces began arriving in England to train for the invasion.

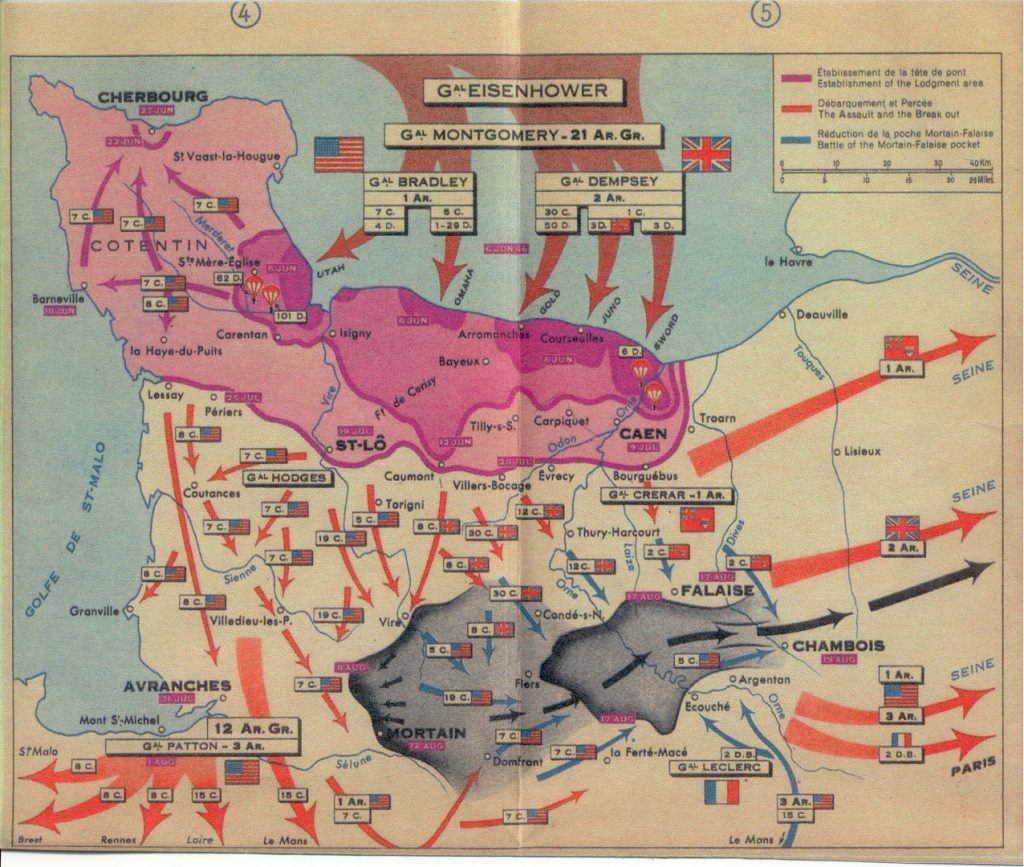

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Allied leaders decided the cross-Channel invasion would occur in the spring of 1944 with American general Dwight Eisenhower as Supreme Allied Commander of the multinational operation. Forces from twelve Allied nations (most occupied by Nazi Germany) would take part. The invasion had to be the most intricately planned military operation in history. Such questions as where and when to land; how many soldiers, tanks, ships, and planes would be needed; what equipment each man had to carry; and the essential question of how to keep this a secret from the enemy were debated and planned. The final plan called for some 156,000 men to land on five beaches on the coast of Normandy: the Americans at Utah and Omaha in the west, and the British and Canadians at Gold, Juno, and Sword. They would be bolstered by parachute and glider landings and supported by some 5,000 ships and 11,000 airplanes.

Planners set the date of June 5, 1944, for the landings, but a storm that day meant it would be too cloudy to bombard German coastal defenses and too windy for men to disembark from landing craft. British meteorologist James Stagg advised General Eisenhower of a temporary break in the weather, clearer skies, and lighter winds, which would potentially allow the invasion to commence twenty-four hours later. With his assault, naval, and air commanders all saying “go,” Eisenhower gave the order.